Musings on Mitigation

Mitigation Horizons

I've concluded that

there are three useful ways to think about mitigating

the effects of Peak Oil and the other Problematique crises humanity is

facing, related to the time horizon under

consideration.

The first is to look for the near-term technologies and behaviours that will promote a softer entry into the coming depletion phase. I count things like hybrids, BEVs, car-pooling, improvements to mass transit and fuel rationing in this group.

The second is to develop approaches that will be useful in the medium term, for supporting "lifeboat" communities or regions: permaculture and urban gardening, a revival of food preparation from scratch, small-scale wind, solar and hydro power, and low-energy living in general.

The long term perspective is more difficult: how to cope with a whole society without enough oil, and possibly having gone through a crash. At this point I don't know what the most useful approaches might be to cope with that scenario, other than explicit knowledge-retention projects designed to guard against the loss of knowledge as well as the loss of capability. It's hard to predict past what is essentially a singularity (though hardly a hopeful one as postulated by Ray Kurzweil). I hope that if we get serious about the relocalization and lifeboat approaches that successful communities might provide nuclei for social regeneration in this phase.

The first is to look for the near-term technologies and behaviours that will promote a softer entry into the coming depletion phase. I count things like hybrids, BEVs, car-pooling, improvements to mass transit and fuel rationing in this group.

The second is to develop approaches that will be useful in the medium term, for supporting "lifeboat" communities or regions: permaculture and urban gardening, a revival of food preparation from scratch, small-scale wind, solar and hydro power, and low-energy living in general.

The long term perspective is more difficult: how to cope with a whole society without enough oil, and possibly having gone through a crash. At this point I don't know what the most useful approaches might be to cope with that scenario, other than explicit knowledge-retention projects designed to guard against the loss of knowledge as well as the loss of capability. It's hard to predict past what is essentially a singularity (though hardly a hopeful one as postulated by Ray Kurzweil). I hope that if we get serious about the relocalization and lifeboat approaches that successful communities might provide nuclei for social regeneration in this phase.

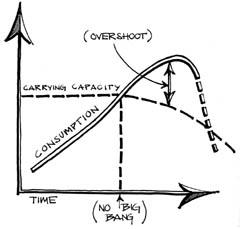

Overshoot

and the Genetic Basis of Human Behaviour

Two ideas underpin

all my

analysis of the looming crisis.

The first is the ecological concept of overshoot.

Overshoot occurs when a population exceeds the long term carrying capacity of its environment. It's not just that there are "a lot of people", as a simplistic definition of overpopulation might imply. It has everything to do with how much of the resource base those people require to live. The ecological niche from which we extract our resources has expanded to become the entire planet. Our species requires not just the renewable resources of that niche but is rapidly chewing up the non-renewable resources as well,. Given those facts, it's obvious that our way of life is unsustainable. If the time horizon for its continuation is now measured in decades it is likewise obvious that we are in overshoot. The extent of the overshoot is debatable, but the mere fact of it is not.

The biggest problem with overshoot (aside from the fact that it always results in a population crash of some degree) is that the underlying resource base is damaged by over-use. When that happens, the population remaining after the decline or crash may not have sufficient resources to rebuild either their numbers or the structure of their ecology. I address this more below in the discussion of adaptive cycles.

I heartily recommend Catton's "Overshoot" and the latest update to "Limits to Growth" for an understanding of the topic, a sobering analysis of why we are already in overshoot, and the inevitable ecological consequences.

The second driver for my thinking is genetics as it relates to to human behaviour.

There appears to be a mechanism built into every reproductive species, from bacteria to flatworms, robins to rabbits, tigers to chimpanzees that favours excess reproduction beyond the replacement rate. It's easy to understand why that is a general rule of nature. In an environment where there are predators this is a survival-positive trait: if a few individuals get eaten, the species isn't threatened. However, when there are no predators, it's catastrophic. Think of the rabbits in Australia. We are like those rabbits: we have no predators except ourselves. The result is a human population that has quadrupled in a century, to which we add over 75 million new members every year.

This drive to reproduce is complemented by a second genetic imperative: the urge to maximize our comfort by accumulating as many resources for ourselves as possible. As long as the population didn't grow and tool use stayed limited this drive also enhanced rather than threatened our survival. Unfortunately, when our brains gave us the ability to build tools to conquer our predators and dig deep into the resource base of our ecological niche, natural selection didn't have enough time to endow us with a corresponding genetically-mediated sense of restraint that might have made this behaviour sustainable.

As a result the only restraints we have on our reproduction rates and resource use come from our intellect. And while intellect is a very powerful tool for manipulating the outside universe, it is extremely weak when it comes to modifying our own behaviour. In the main, genetically encoded behaviour patterns tend to rule the day.

The planetary destruction (and accompanying self-destruction) we are starting to recognize is in large measure inevitable due to the collision between the immovable rocks of these two genetic imperatives and the irresistible force of our prodigious cerebral cortex. I think we as a species are in many ways at the mercy of our genetics in terms of both our reproductive behaviour and our consumptive behaviour. As a result I deeply believe that we are heading for a significant die-back of the human species over the next 50 to 100 years, as our behaviour drives us deeper and deeper into overshoot on an already ravaged planet.

For those with a need to look Mother Nature square in the eye, Reg Morrison's "The Spirit in the Gene" provides an unflinching look at this dilemma.

The first is the ecological concept of overshoot.

Overshoot occurs when a population exceeds the long term carrying capacity of its environment. It's not just that there are "a lot of people", as a simplistic definition of overpopulation might imply. It has everything to do with how much of the resource base those people require to live. The ecological niche from which we extract our resources has expanded to become the entire planet. Our species requires not just the renewable resources of that niche but is rapidly chewing up the non-renewable resources as well,. Given those facts, it's obvious that our way of life is unsustainable. If the time horizon for its continuation is now measured in decades it is likewise obvious that we are in overshoot. The extent of the overshoot is debatable, but the mere fact of it is not.

The biggest problem with overshoot (aside from the fact that it always results in a population crash of some degree) is that the underlying resource base is damaged by over-use. When that happens, the population remaining after the decline or crash may not have sufficient resources to rebuild either their numbers or the structure of their ecology. I address this more below in the discussion of adaptive cycles.

I heartily recommend Catton's "Overshoot" and the latest update to "Limits to Growth" for an understanding of the topic, a sobering analysis of why we are already in overshoot, and the inevitable ecological consequences.

The second driver for my thinking is genetics as it relates to to human behaviour.

There appears to be a mechanism built into every reproductive species, from bacteria to flatworms, robins to rabbits, tigers to chimpanzees that favours excess reproduction beyond the replacement rate. It's easy to understand why that is a general rule of nature. In an environment where there are predators this is a survival-positive trait: if a few individuals get eaten, the species isn't threatened. However, when there are no predators, it's catastrophic. Think of the rabbits in Australia. We are like those rabbits: we have no predators except ourselves. The result is a human population that has quadrupled in a century, to which we add over 75 million new members every year.

This drive to reproduce is complemented by a second genetic imperative: the urge to maximize our comfort by accumulating as many resources for ourselves as possible. As long as the population didn't grow and tool use stayed limited this drive also enhanced rather than threatened our survival. Unfortunately, when our brains gave us the ability to build tools to conquer our predators and dig deep into the resource base of our ecological niche, natural selection didn't have enough time to endow us with a corresponding genetically-mediated sense of restraint that might have made this behaviour sustainable.

As a result the only restraints we have on our reproduction rates and resource use come from our intellect. And while intellect is a very powerful tool for manipulating the outside universe, it is extremely weak when it comes to modifying our own behaviour. In the main, genetically encoded behaviour patterns tend to rule the day.

The planetary destruction (and accompanying self-destruction) we are starting to recognize is in large measure inevitable due to the collision between the immovable rocks of these two genetic imperatives and the irresistible force of our prodigious cerebral cortex. I think we as a species are in many ways at the mercy of our genetics in terms of both our reproductive behaviour and our consumptive behaviour. As a result I deeply believe that we are heading for a significant die-back of the human species over the next 50 to 100 years, as our behaviour drives us deeper and deeper into overshoot on an already ravaged planet.

For those with a need to look Mother Nature square in the eye, Reg Morrison's "The Spirit in the Gene" provides an unflinching look at this dilemma.

Adaptive Cycles and Resilience

Given the inherent morbidness of the conclusion that human decline is inevitable, one area of research that is very heartening is the relatively new field of complex adaptive systems. Recent research into ecosystems has generated some useful understanding about adaptive cycles and system resilience.

The essential concept is that all complex adaptive systems (of which human civilization is one) go through looping cycles as they grow and decline. On the way up the front of the cycle as the system grows, it gains in integration, efficiency and brittleness. The brittleness combined with resource depletion or negative outside influences pushes the system over the top of the loop and into decline. During decline the system loses integration/efficiency/brittleness and gains modularity/inefficiency/resilience. The degree of resilience a system retains as it grows determines how steep the inevitable decline will be.

Once the system has regained enough resilience during the decline, it can loop around the bottom of the cycle and growth can restart. There is a caveat - the system will not have access to the same resources that were available to fuel the previous growth cycle because they may have been used up. As a result the character of the system will be different the next time around because it will have to find different resources. It will, however, re-grow unless the ecological niche has been catastrophically damaged and extinction results. I don't think it will go that far with us.

For me, this formulation is the perfect anodyne for the paralyzing despair that can result from perceiving the progress of civilization as a simple two-dimensional journey of growth, elaboration, crisis, collapse and disappearance,. While it may for some resonate uncomfortably of the ideas of resurrection, reincarnation and the Wheel of Karma, it nonetheless identifies a perfectly naturalistic context within which we can find a home for much of the human experience.

These concepts are addressed in Thomas Homer-Dixon's "The Upside of Down", and for me were the most useful insights in the book. .Further information can be found on the net in the work of the Resilience Alliance.

Conclusion

All in all I'm perversely hopeful, but I want to make sure I don't generate any false expectations about the future, or encourage magical thinking. Business as usual, as we've come to define it during the last 100 years, is utterly unsustainable, and is unlikely to last longer than another couple of decades. Any mechanisms that attempt to maintain it beyond that will risk making the coming decline worse by stretching out the growth phase of the cycle we're in. That's why I tend to discount some technologies (e.g. biofuels, solar power and hybrid cars) that others view as helpful.

I know all this may sound a bit gloomy and fatalistic, but I strongly believe that these conclusions are amply justified by the evidence. We have a lot of work in front of us, no matter how we decide to approach this. The only thing that is unacceptable is to sit still.